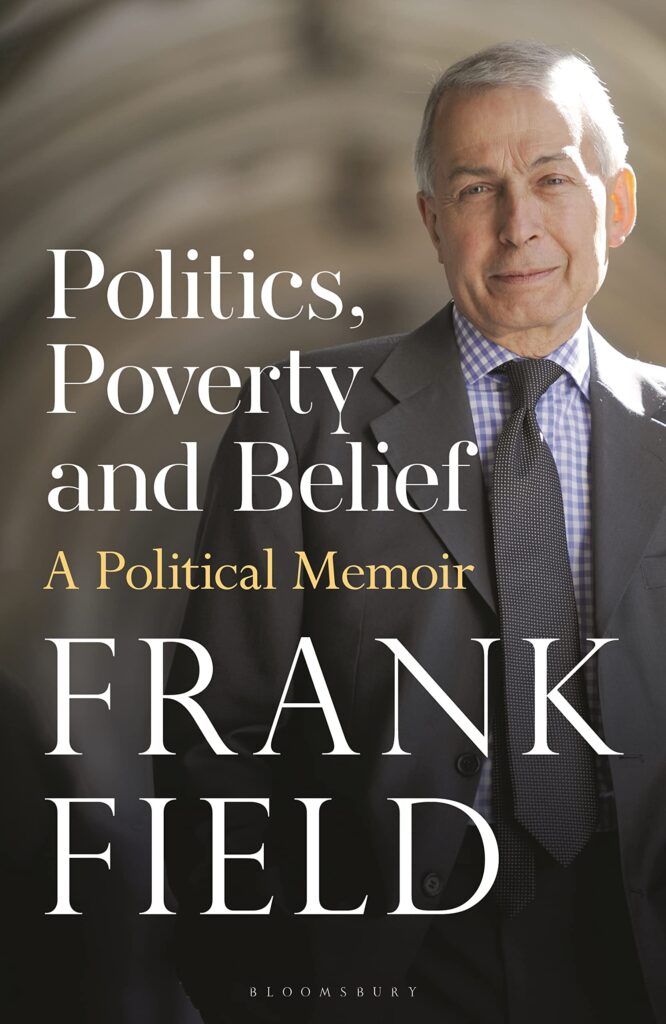

Frank Field’s Politics, Poverty and Belief

208 pages ISBN 978-1399408394

Only £3.99 for Kindle at present (May 2023)

On 16 June 1986 Frank Field, then MP for Birkenhead, kindly came and spoke to the youth group at St Andrew’s, Bebington after being interviewed about his faith and politics in our 6.30 pm evening service. I was the curate who invited him to come and gave you a lift home to Birkenhead afterwards. He spoke very well in the service about Jesus’ teaching on the kingdom of God and its implications for national and political life, and the youth group found him inspiring as a positive model of Christian engagement in public life. It is, then, a delight to read this final book in which he reflects on his faith and its impact on his political life. Here’s a key observation at the end of the final chapter, which sums up much which Lord Field (as he now is) says:

Here, then, is the basis of my Christian approach to politics. My vision has been dominated by my views on human nature. We are all fallen creatures, but open to be redeemed. One role of politicians is to offer programmes that achieve this objective. Another way of seeing this Christian cornerstone to politics is in the creation of programmes that work with, rather than against, this grain of human nature (page 154).

The first part of the book is a kind of intellectual and spiritual autobiography, ‘Ideas and Images’ (chapters 1–6). I was struck by his observation that the church he belonged to as a teenager, while it introduced him to worship and prayer of an Anglo-Catholic tradition, ‘it didn’t teach me any idea whatsoever of the Catholic faith…all I know is that during my crucial early years I had no vision of the world into which I could try and fit my life’s actions (pages 23, 24). While studying politics at Hull University he began to reflect more, and his observation looking back is that ‘The right is forever overemphasizing our fallen nature, to the exclusion of any idea about our redemption. Likewise, the left is overwhelmingly prone to stress that aspect of our character that has been redeemed—not even in a state needing redemption—and does so all too often at the exclusion of the fallen side of our nature’ (page 31). This is an acute observation, and led him to seek to develop policies which self-interested altruism is the way to proceed: for example, by providing a National Insurance scheme into which people pay during their working lives knowing that they themselves will benefit from it at a later date. Along this path, he discovered Jesus’ teaching about the kingdom of God, and I remember this being his theme when we interviewed him in church about his Christian basis for political involvement. He also sees democratic freedoms as rooted in the covenantal freedom given to Israel under Moses (page 47).Thus:

Each campaign, and indeed every campaign I have tried to promote over the past 50 years, has been about extending freedom, either in the sense of being free from arbitrary power or in the positive sense of having the support to develop our best selves. Freedom has therefore been central to the whole of my political activity. (page 52)

The second part of the book looks at some of the campaigns Lord Field has been involved in, fighting poverty, the sale of council houses and the redistribution of wealth, and arguing for a minimum wage. On the latter, as a Labour MP, he found himself opposed by most of the Labour party and especially the unions, as well as the Tories and the Liberals, but won the argument to the extent that a minimum wage is now uncontroversial across the UK political spectrum. Lord Field also campaigned against hunger, a major issue in his Birkenhead constituency, modern slavery, and global warming. In each of these campaigns his Christian faith and motivation is evident. He has also worked on issues aiming to prevent children from poor families becoming poor adults through addressing issues of early years care, parenting, and schools.

He turns then to the collapse of what he calls ‘the culture of respect’, arguing that mutual respect among people and groups is a left-wing cause. He expresses sadness as ‘the rich deposits of ethical values left behind as the great tide of evangelical Christianity receded from its near-domination of English culture’ (page 117) in the Victorian period.

Lord Field twice experienced the extreme left seeking to unseat him from his post as MP for Birkenhead. He managed to survive the assault of Militant in the late 1970s, but lost out when Momentum, during Jeremy Corbyn’s incompetent leadership of the Labour party, renewed the attack. This led to Lord Field resigning as MP in 2018, and then being thrown out of the Labour party.

This is a fascinating book by a remarkable man. He has not broadcast his Christian faith throughout his life, although it is clear from this account that that faith has been the driver of his political life and actions. It is testimony to the kind of person—and Christian—that Lord Field is that Lord Brian Griffiths and his wife Rachel encouraged him to write this book, for they are Tories and evangelical Christians, and thus from very different political and Christian traditions to Lord Field. This is a book worth reading for Christian people interested in politics.